Kameelah Janan Rasheed and Corey Tegeler describe their collaboration, Mapping the Spirit (Credit: Liz Sanders)

photographers, curators, activists, theorists, creative technologists present on collaborative documentary practices

WEDNESDAY, JULY 5 | BY HANUL BAHM

special to The Alliance

On Thursday, June 8, Magnum Foundation presented Photography Expanded, a full day of presentations and panels on collaborative documentary practices. An energetic crowd filled the Cooper Union’s Rose Auditorium in New York City; there, they were treated to a sweep of contemporary practices by photographers, curators, activists, theorists and creative technologists. The foundation did a knockout job assembling varied sets of presenters, each with a distinct approach to the document and documentary. For those who could use a jolt of inspiration, the entire day is archived as a video stream.

Magnum Foundation launched in 2007 to support independent, long-form visual storytelling on social issues. Their aim—to expand creativity and diversity in documentary photography—is realized through grantmaking, mentoring and creative collaborations throughout NYC and beyond.

Documentary itself has long been a delicate dance of consent, the photographer’s value to the photographed not always clear. I hoped the day would answer some lingering questions: Who gets to speak for whom, and why? Toward what ends?

With the day’s word being “collaboration,” I looked upon the empty stage, pre-symposium, with equal measures hope and wary. “Collaboration,” a term so full of goodwill, can take on strange cadences, even go as far as being code for unconscious bias and power dynamics. Documentary itself has long been a delicate dance of consent, the photographer’s value to the photographed not always clear. I hoped the day would answer some lingering questions: Who gets to speak for whom, and why? Toward what ends?

But maybe the questions are moot. Documentary seems to belong to everyone now. Documentary is the selfie. It’s the concerned bystander pressing “record.” It’s a repost of a Tweet, an SMS text photo of someone’s niece, birthday, life event. And according to Magnum Foundation, it’s no longer just pictures or a sequence of pictures. Documentary is a multi-contributor web archive. It’s Starting with Questions Not Answers, a zine edited and assembled by Mark Strandquist.

Executive Director Kristen Lubben opened the day by insisting collaboration is “especially important in times of upheaval.” She asked us to consider photography’s role in collective action, public space, radical economies and challenging notions of authorship.

Attendees of Photography Expanded at the Cooper Union Rose Auditorium (Credit: Liz Sanders)

Collaborating Across Disciplines

Three pairs of Magnum Foundation Fellows then presented collaborations, each interpreting this year’s theme of religion. Up first were photographer Kameelah Janan Rasheed and creative technologist Corey Tegeler with Mapping the Spirit. Spurred by her father’s conversion to Islam, Kameelah started exploring the black religious experience in America beyond the church. She began by photographing subjects from the Moorish Science Temple of America, a faith-based movement borne out of post-Great Migration Chicago. To this, she added video, audio, long-form interviews and archival documents.

With Magnum Foundation’s support, she teamed with Corey to present her collection in ways that supported revision and inbound story material. Though he didn’t always know what Kameelah would share ahead of time, the constraint challenged Corey to design a web platform that could absorb new content. Corey shared that he aimed for design aesthetics and customization features, more like web apps and less like institutional digital archives.

Photographer Yael Martinez and graphic designer Orlando Velazquez of Mexico presented The Blood and the Rain (Petition de Lluvias), a meditation on absence, invisibility and letting go. Traveling to Zitlala in Guerrero, Mexico, the two paired with anthropologist Julio Glockner to express the “relationship between nature, God, ritual and rain.” Yael found himself facing a challenge: he was able to secure access to some, but not all, of the rituals he sought to shoot. Merging disciplines allowed both artists to fill in the blanks, giving form to presences and occurrences implied but unseen.

Photographer Oscar Castillo and programmer Sam Lavigne presented The Crescent x the Stars x the Cross, an online photo project looking at Islam in France. The series’ dynamic, tapestry-like architecture can be found at thecrescentproject.com.

Crescent Project artwork by Oscar Castillo (Credit: Hanul Bahm)

Unknown Unknowns

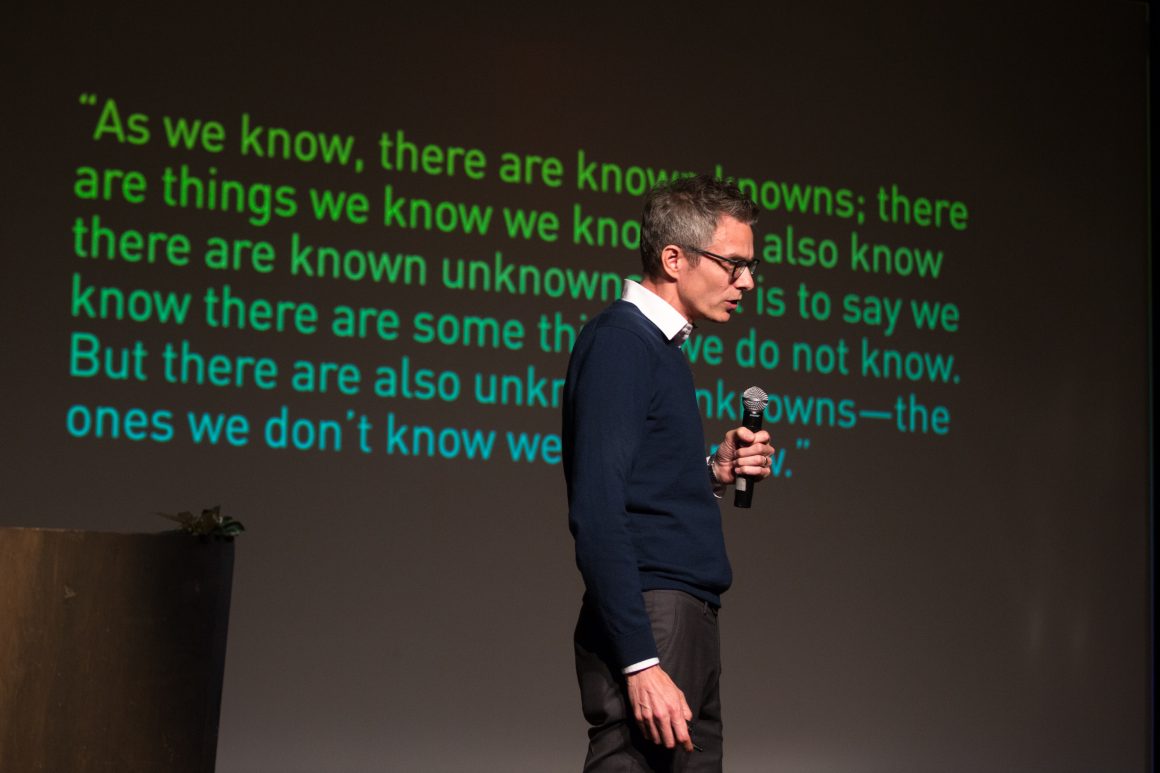

Jamer Hunt, Director of Transdisciplinary Design at Parsons, introduced the idea of “unknown unknowns.” Repurposing a quote from former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, Jamer presented a schema for knowledge and ignorance:

“As we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns, that is to say, we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know.”

Jamer Hunt presents Donald Rumsfeld’s “unknown unknowns” quote (Credit: Megwen Cao)

Applying this to the creative process, Jamer invited us to create the conditions conducive for “unknown unknowns,” where discovery occurs. His guidelines:

- – Allow yourself to be in unfamiliar territory or to enter uncertainty

- – Be open to unanticipated outcomes

- – Collide different disciplines—disrupt your way of seeing the world by collaborating

- – Decentralize authority and control—give it away to someone else and see what emerges

- – Encourage mutations through experimentation

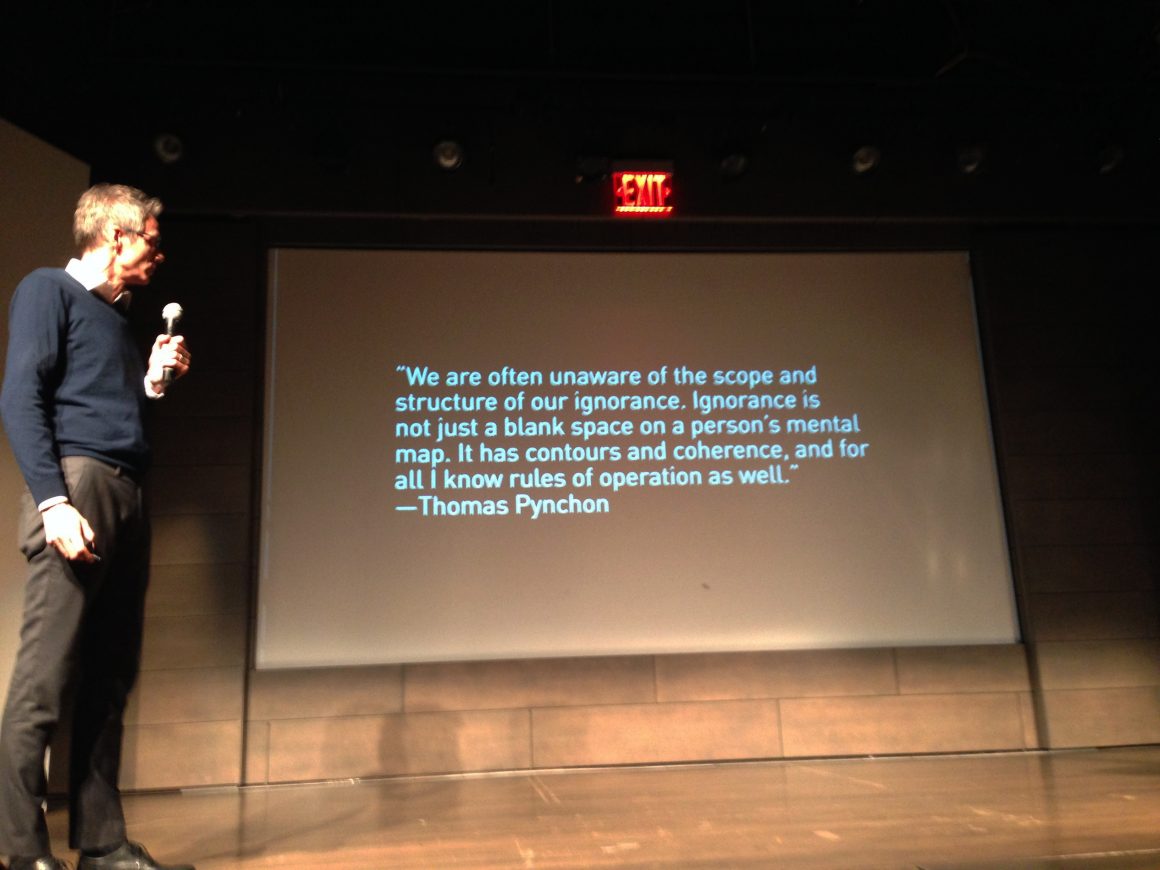

“We are often unaware of the scope and structure of our ignorance. Ignorance is not just a blank space on a person’s mental map. It has contours and coherence, and for all I know rules of operation as well.” — Thomas Pynchon

Jamer warned that “what we don’t know is not simply a blind spot. It’s structure. It’s systemic.” He then presented two beautiful, instructive quotes from theorists Thomas Pynchon and Kenneth Burke:

“We are often unaware of the scope and structure of our ignorance. Ignorance is not just a blank space on a person’s mental map. It has contours and coherence, and for all I know rules of operation as well.” — Thomas Pynchon

“The poor pedestrian abilities of a fish are clearly explainable in terms of his excellence as a swimmer. A way of seeing is also a way of not seeing — a focus upon object A involves a neglect of object B.” — Kenneth Burke

Jamer Hunt presents a Thomas Pynchon quote on ignorance (Credit: Hanul Bahm)

Improvisation and the Unbound Frame

Emma Raynes, Magnum Foundation’s Director of Programs, moderated a panel on inviting vulnerability and play into our works.

Boston-based Eric Gottesman shared a working definition of collaboration “as a rejection of what the photographer wants to get out of it.”

Eric Gottesman presents photos from If I Could See Your Face (Credit: Mengwen Cao)

As a photographer covering Ethiopia’ s HIV epidemic during from 1999 to 2014, initially on a Hart Fellowship, Eric saw that his subjects often lived in the shadows of shame. Before antivirals had hit and activists and policymakers could create a strong public health infrastructure, HIV carried a broad notion as epidemic but a vague sense of who was being infected. No one wanted to step up and be its face.

In his collaboration with Yawoinshet Masresha, a counselor who started the NGO Hope for Children, Eric learned not to frame questions in a past tense, but in a conditional or future tense. Yawoinshet, who worked with populations dealing with HIV and conflict, spoke in a way that involved the kids’ imagination, shifting the conceit of their doc work, “not as a past event but as a dream of a future event.” They co-founded the Sudden Flowers group and created photo assignments, asking questions such as: “Who would you be if you weren’t who you are?” One young boy responded, “I would be an old man,” and posed as one. Make-believe became a tool to break the limitations of representation in photography.

For the past six years, Eric has produced the Oromaye project, a constellation of projects based on a formerly banned novel. Oromay’s author, Baalu Girma, was assassinated for writing the novel, now a bestseller praised for its dissent. Eric reprised and staged passages of the novel with Ethiopian filmmakers, cultural producers and non-actors.

Patterns of Collaboration

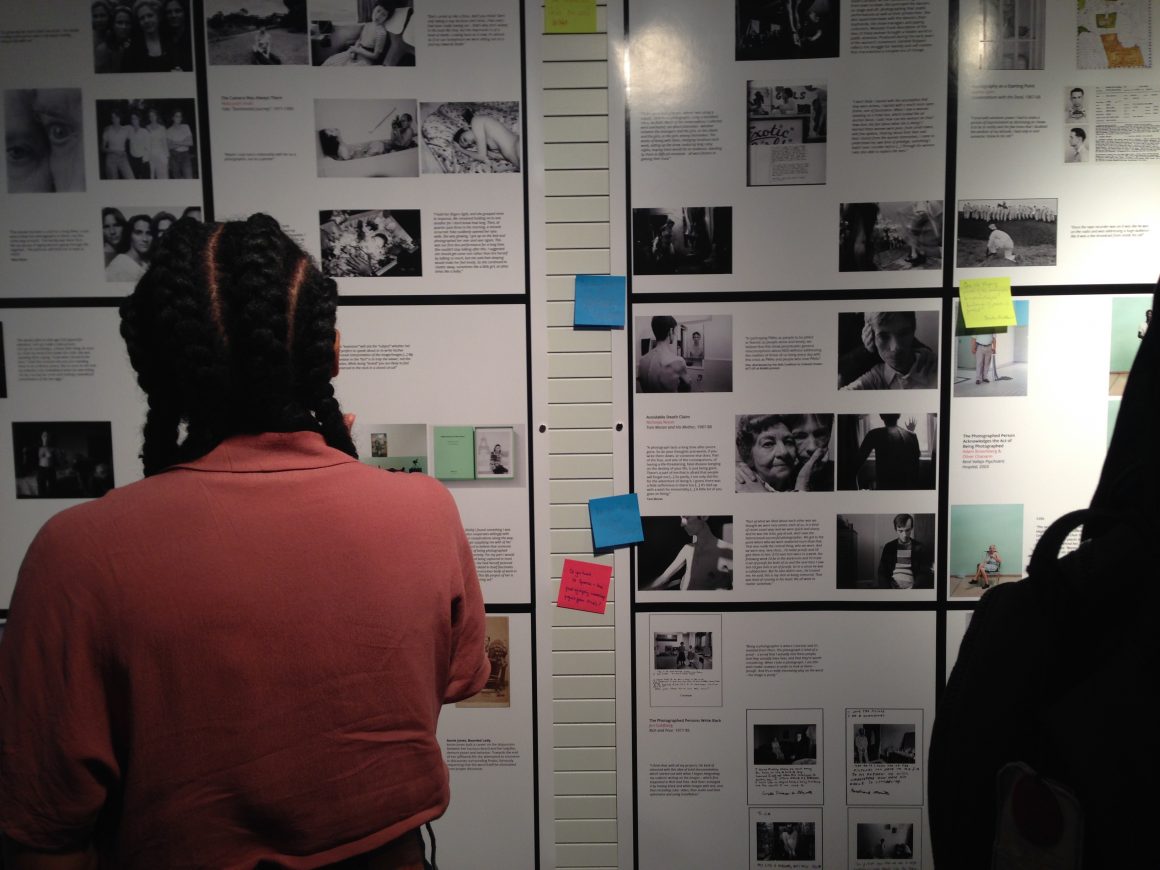

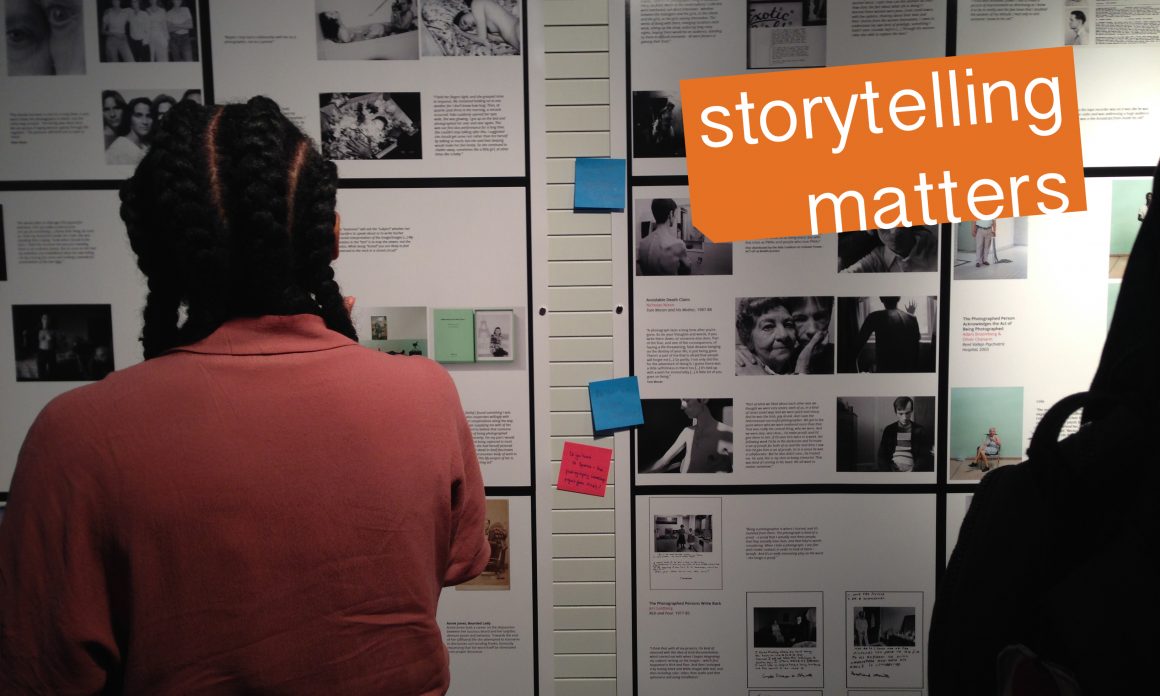

Photographers Susan Meiselas and Wendy Ewald introduced On Collaboration: Revisiting the History of Photography. Conversations on what had inspired their own collaborative practices had, in time, evolved into temporal exhibits, a live lab, workshops and a pop-up project involving university students. Susan and Wendy mounted three of their Co-Lab clusters in the Cooper Union atrium, inviting post-it feedback from symposium attendees.

An attendee studies a Co-Lab cluster, mounted by Wendy Ewald and Susan Meiselas (Credit: Hanul Bahm)

A “project on mapping,” On Collaboration looks at some of photography’s most iconic projects and charts their characteristics. Susan and Wendy shared some core projects, prefacing them with signifiers. Among them:

1. The Photographed Person was Always There: Couple Emmet and Edith Gowin reveal what it’s like, relating to the photographer, when he’s both subject and author.

2. The Photographer Seeks to Reshape the Authorial Position through the Photographed Person’s Collaboration: Jim Goldberg’s Rich and Poor, a classic portrait series portraying income inequality, includes the subject’s handwritten commentary on his images of them.

3. Collaboration Precedes Iconization: For Dorothea Lange’s photo, Migrant Mother, Lange convinced Florence Owens Thompson to be photographed, to make her and others’ conditions known. Thompson posed herself as the figure of poverty, but never saw the picture until 1978.

4. Potentializing Violence: Marc Garanger’s Algerian Women is a 1960 photo essay of Muslim Berber women during the Algerian War; the women had neither choice nor consent in the image making. Forty years later, Garanger located the women, offering his photographs as documents for their family histories.

5. Co-Archiving: Thomas J. Calloway and W.E.B. DuBois’ Negro Exhibition included 500 photographs of Atlanta’s black middle class communities for the 1900 Paris Exhibition. The collected photographs portrayed “present conditions” of African Americans, challenging the race science of the time.

6. When a Community is at Stake: In her series Faces and Phases (2006-2011), Johannesburg photographer and visual activist Zanele Muholi created over 300 images of South African LBGTQ women. Muholi’s mission is “to re-write a black queer and trans visual history of South Africa” and to shed light on hate crimes.

Wendy and Susan shared that, along with collaborators Ariella Azoulay and Laura Wexler, they continue to search for “the right form” for On Collaboration. Among those being considered are a live lab, exhibits, a book or online site. “We want to map the history and find the means for more people to continue contributing to it.”

Reflections on Collaboration

Cultural organizer Mark Strandquist (Credit: Liz Sanders)

Cultural organizer Mark Strandquist added a bit of wonderful, analog interactivity to the symposium. He breathlessly shared that he had stayed up until 3 a.m., putting together the zine that each attendee had in her seat. The zine, called Starting with Questions Not Answers, compiles first-person thoughts on collaboration from the day’s presenters as a shareable resource.

Place-Based Storytelling

In a panel called Making Place, Holding Space, Magnum Foundation’s Noelle Flores Theard introduced two organizations: Appalshop, a 48-year-old multimedia arts organization based in Whitesburg, KY, and The Point, a community development corporation in the Hunt’s Point section of the Bronx. Both organizations talked about place-based storytelling as well as creative placemaking.

Founded on the backdrop of Central Appalachia’s coal-mining industry, Appalshop set out to use media to address complex issues facing the region: a declining coal economy, a legacy of environmental damage, high unemployment rates and poor educational opportunities. Since its beginnings, Appalshop Films has created over a hundred documentaries. Appalshop’s Appalachian Media Institute (AMI) helps young people apply media production skills toward asking, and beginning to answer, critical questions about themselves and their communities.

Kate Fowler of Appalshop describes the context for its founding in 1960s Appalachia (Credit: Hanul Bahm)

Josh Collier, a 2015 AMI Summer Documentary Institute intern, co-created the film Go Your Own Way. Josh shared: “My family is from the counties surrounding Appalshop. My great-great uncle Oaksie was the subject of an Appalshop film in the 1970s, but my family’s affiliation with the organization has dwindled.

“Over the eight-week course, I learned more about the place my family has always claimed as home. The experience uncovered complexities that residents of the region struggle daily to understand; it showed that Kentuckians are much less homogenous than perceived to be.”

Onstage, AMI Director Kate Fowler referenced “Stranger with a Camera,” a 2000 Appalshop film directed by Elizabeth Barret. The film revisits 1960s Appalachia, when the world’s filmmakers were making a case study out of its poorest residents—a precursor for the economic justice movement. Community backlash ensued; questions were raised as to whether the images exploited stereotypes of Appalachian people. In 1967, tensions came to a head when eastern Kentuckian Hobart Ison shot and killed Canadian doc filmmaker Hugh O’Connor. “Stranger with a Camera” revisits the tragedy while examining issues of identity and representation.

Kate: “When you tell a story, you have to live alongside it. It changes the dynamic about how we work and what we say about the place.”

“When you tell a story, you have to live alongside it. It changes the dynamic about how we work and what we say about the place.” — Kate Fowler, Director, Appalshop’s Appalachian Media Institute

Danny Peralta, THE POINT’s Executive Director, said his organization’s work was about “challenging the norms of how people perceive the South Bronx.” Danny wants to see Bronx residents be the makers of their own future.

A locus for creative placemaking and justice work, THE POINT offers afterschool and teen programs, as well as arts enrichment and photography in partnership with the International Center of Photography (ICP). THE POINT tackles systemic issues, too; they incubate small businesses and advocate for environmental justice, brownfield development and public health. Part of THE POINT’s success lies in it willingness to collaborate and form coalitions with city agencies, nonprofits and private universities.

Danny stressed that community-based initiatives were where the real work of social change was being done, ahead of the curve of what’s being hatched as research at Columbia University. The comment was met with cheers and applause.

Photographer Roy Baizan presented works from “NYHC/Hydro Punk project,” a photo essay on the underground music scene developing out of basements in the Bronx. “Young people want alternative narratives of who they are,” said Roy, a Bronx-raised photographer currently on staff at ICP and the Bronx Documentary Center.

Roy Baizan presents his images from the “NYHC/Hydro Punk” project (Credit Hanul Bahm)

Alternative Forms of Authorship

Gemma-Rose Turnbull (standing) co-presents with Zohar Kfir, Nina Robinson and Sol Aramendi (left to right) (Credit: Liz Sanders)

Gemma-Rose Turnbull led an inspired panel called Disruptive Participation and Radical Listening, co-presented with Sol Aramendi, Nina Robinson and Zohar Kfir. A lecturer of photography at Conventry in England, Gemma-Rose runs a website, “Photography is a social practice.” Committed to disseminating alternative forms of authorship, Turnbull observed that “photography heroizes the single auteur,” but that active listening “might set conditions for a more distributed authorship.”

“Listening is one component of a process. A huge component is to let people speak openly and clearly about what they feel, want, need,” Gemma-Rose said. The panelists stressed the importance of giving subjects an active say in the storytelling’s structure and parameters.

Sol Aramendi, a Queens-based artist by way of Argentina, sees photography as a tool that “lets communities build power for themselves.” She works closely with immigrant and labor communities in New York and beyond. Among other projects, Sol shared Jornaler@, an app she co-developed out of a series of photo workshops, work safety dialogues and publications between union workers and day laborers (jornaleros). Sol saw an opportunity to bring two groups pitted against one another to work toward a common goal: wage theft. Jornaler@ collects personal data and provides labor rights education.

“Putting on a headset and tuning out the rest of the world… is a commitment to listening.” — Zohar Kfir

Nina Robinson, a photographer and educator based in New York and Arkansas, shared images from her phototherapy program for senior citizens in Dalark, AK. What started as a beginning photography class became sharing personal photos and taking pictures of one another. As an exercise, Nina would present a photo to her students and ask, “What do you see? What do you feel?” Images of first houses, wedding days and others memories allowed students to talk about race, class and politics.

Zohar Kfir, a New York-based artist, presented TESTIMONY, an interactive VR doc about survivors of sexual assault. Zohar sought to create a platform for rape victims to share their journeys to healing. “Putting on a headset and tuning out the rest of the world… is a commitment to listening,” said Zohar.’’

Asked by Gemma-Rose how the artists went about eliciting openness, Nina said she volunteered her own personal stories to encourage people to open up.

Sol: “For me, it was always about making something. Making grants, posters, etc. always related to labor. It’s been the best way to speak, to have a conversation, to insert myself in the group.”

Of Publics, Places, and Politics

Nato Thompson and Tiona Nekkia McClodden (Credit: Liz Sanders)

Philadelphia-based cultural organizer Nato Thompson and artist Tiona Nekkia McClodden closed the day on a powerful plea to restore the soul back to the image.

Nato, Artistic Director of Creative Time, observed that “socially engaged discourse is no longer on the outside… it is everywhere.” He shared that artist Mark Bradford is being represented at this year’s Viennale, while Budweiser aired their immigrant tale commercial and Audi their commercial on gender equity during the Superbowl.

“There are more foundations giving to the arts, more people on payroll whose job it is to save the planet, yet the political climate in my lifetime has gotten worse and worse. I’m 45 years old. I have not seen an effective social movement in my life. That’s a lot of years.”

Nato cautioned that art and activism can fall prey to name-dropping careerism, adding: “We are in an arm’s race for images. People want affective images, an image with a soul.”

Artist Tiona Nekkia McClodden shared that much of her work had to do with the act of memory and re-memory. Her works explore queer blackness and Black culture, whose collective inheritance, ideas, values and experiences she described as “Black Mentifact.” Regarding these artifacts and beliefs that are in our heads and forgotten by time, Tiona explains, “There’s a lot that happened in the past that’s still relevant today.” To shore against erasure, Tiona emphasizes past lives and events over introducing new narratives.

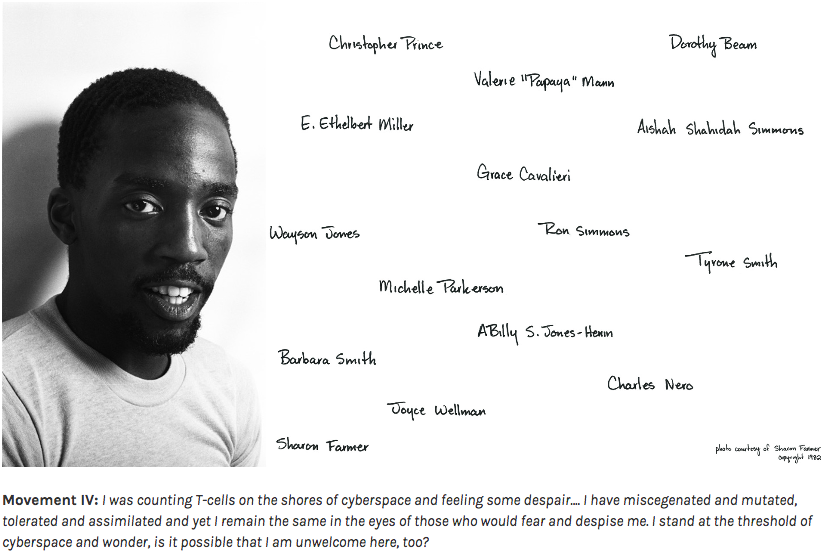

From Tiona Nekkia McClodden’s “Affixing Ceremony: Four movements for Essex.” © 2015

Tiona’s online arts tribute, Affixing Ceremony: Four movements for Essex, explores the life and art Philadelphia poet Essex Hemphill, who died of AIDS in 1995. Beloved and frequently brought up in conversations by the local arts community, Tiona gathered people’s memories of Essex, as well his works. A powerful quote from On the Shores of Cyberspace prefaces Tiona’s tribute. Also featured are audio interviews of friends and artists reflecting on Essex’s life.

Nato talked about the “untenable crisis of the whiteness of our institutions,” stating that most arts-supporting platforms are white-led. Attributing a failure of trust among Philadelphia arts institutions toward surrounding communities, Tiona said that local artists of color received far less coverage and support.

“The work needs to resonate with the communities. If the art world gets it but the people represented don’t, it has somehow failed,” Tiona said. A first-generation artist with a family lineage tied to domestic and military workers, Tiona said she takes the privilege of being an artist seriously. She also extolled self-care, echoed by other panelists throughout the day.

After returning home, I thought of the people who had bent me toward documentary. These people, who shaped my worldview more than the news, who had trained their attention on looking outside themselves and seeing the writing on the wall.

My mind also turned to Nas, the legendary rapper who put Queensbridge, just a few miles from the Cooper Union, on the map. His albums could be considered documentary. So could his Facebook wall: Nas regularly posts curated history, headlines and items of interest. Recently he posted a prom teen’s response to fat shaming and an article on the uphill battle for internet access in Africa. He also posts personal photos that, in sum, act like a storybook of his collaborators and extended family.

My mind also turned to Nas, the legendary rapper who put Queensbridge, just a few miles from the Cooper Union, on the map. His albums could be considered documentary. So could his Facebook wall: Nas regularly posts curated history, headlines and items of interest. Recently he posted a prom teen’s response to fat shaming and an article on the uphill battle for internet access in Africa. He also posts personal photos that, in sum, act like a storybook of his collaborators and extended family.

In 2017, documentary belongs to everyone, as it has all along. If documentary has, on some level, always been about the courage to step into others’ lives, open shutter and free of concepts, then I can’t think of a more vital practice for everyone to own.

Photography Expanded exposed me to the depth and current that’s become collaborative, formalized documentary. It let me to listen to some of its brightest and committed practitioners. What Magnum Foundation pulled off was, by any measure, a tour de force of organizing and curating.

I appreciated Nato’s reminder that an image’s worth hinged on its capacity to stir people. How did we come to forget that? But, as Nato also raised, image-making has become an act of social capital. In a time of when there’s so much pressure on creators to market their image(s), I wondered how this shifted, or reinforced, entrenched paradigms on our field.

The fundamental collaborative relationship in documentary is still between the represented and the photographer. Had anything changed in that dynamic? I thought of the disconnecting acts that had become standard in our field. Someone with more resources and social capital, often describing someone with far less. Highly aestheticized images. The opportunities to create being correlated to career bona fides, fellowships, affiliation. Describing our work in concepts that would likely alienate those portrayed, in circles where none are present. If doc subjects are documentarians’ currency for upward mobility, then what was being offering them in return… exposure? Was that enough?

“The work needs to resonate with the communities. If the art world gets it but the people represented don’t, it has somehow failed.” — Tiona Nekkia McClodden

I’m glad to be living in a time when formal and informal images can be equally appreciated and share space in the world. I’m glad we’ve shifted from praising auteurs to praising the widening and group genius that collaborations can be. But maybe we should pause on conferring greatness for a moment.

More than the idea of collaboration, Photography Expanded left me with a sense of urgency toward ownership. For every person and every body to know that their take and equity in any given situation, matter—because it does.

—

Special thanks to Magnum Foundation’s Noelle Flores Theard and Simone Salvo, as well as photographers Liz Sanders and Mengwen Cao, for their contributions toward this blog.

Filmmaker and writer Hanul Bahm creates documentary photography, video and online projects. She’s also worked for the Aperture Foundation, Vibe Magazine, Sundance Institute and Bay Area Video Coalition, helping to further the field in different capacities.

STORYTELLING MATTERS is an Alliance blog series featuring original and curated writing and photography about global story culture and innovation in the hopes of facilitating conversation about the ethical and responsible use of creative technologies in community. If you have a story to share for the series, let us know! creative@thealliance.media

Leave a Reply