By Imani Jacqueline Brown

By Imani Jacqueline Brown

Imani Jacqueline Brown, an Alliance Creative Leader, is a New Orleans native, artist, activist, researcher, and writer. Her work attempts to expose the layers of oppression, injustice, resistance, and refusal that make up the aggregate of our society’s foundation stones. Imani believes that art can drive policy and orients her practice toward the ever-elusive flicker of justice on the horizon, knowing that our world cannot find balance until social, ecological, and economic reparations are won. Imani is currently a Master’s candidate at the Centre for Research Architecture, Goldsmiths, University of London. She is a co-founder of Blights Out, a collective of artists, activists, and architects working to demystify and democratize development in post-Katrina New Orleans, and a core member of Occupy Museums, an artist/activist collective formed in 2011 during Occupy Wall Street to challenge the commodification and financialization of art and culture. In this piece, Brown upends the traditional narrative of the role of the artist in society and tells a whole other kind of story.

Spring is often a time for reflection and renewal. I’m thinking about how 2017 ended with the implementation of a ban on people from seven “Muslim” nations, and journalists mourning the beginning of the end of the American Century, a celebrated period in the short history of American Exceptionalism catalyzed by the dropping of the Atomic Bomb. 2018 ended with the Department of Defense’s Strategic Command––the department that oversees our nuke stockpiles––tweetinga New Year’s warning that they were #ready to “drop something much, much bigger” than New York’s Times Square ball. (#PeaceisourProfession, they quipped in near perfect Doublespeak, a dialect of George Orwell’s Newspeak.) It is now 2019, year three of Donald Trump’s presidency. This is a year that began with a prolonged government shutdown over the construction of a $5 billion border wall to “defend” the nation from the “threat of illegal immigration.” National emergency: Declared.

What then, is the real emergency?

The veil of the American Dream is slipping and more Americans than ever are coming to realize that the external enemy we have been conditioned to fear since 9/11 was a distraction from a closer threat: ourselves. Since Donald Trump entered the political arena in 2015, use of the word “fascist” as a descriptor of an emergent quality in American politics has creeped from domain of the “fringe” left, who saw the specter of fascism reflected in post-9/11 lawfare, to mainstream political discourse. As someone who counts herself among the ranks of the “fringe” left, I am relieved that we are finally having a conversation about the fascist taint in America. But I don’t want our period of reflection to be consumed by debates about whether Trump is a fully-fledged fascist or simply a proto-fascist using fascist rhetoric. I’m worried about the rest of us. In his 1915 Doctrine of Fascism, Mussolini wrote that “besides being a system of government [fascism] is also, and above all, a system of thought.” Which comes first, the system of government or the system of thought? I propose the latter––that fascism doesn’t spontaneously appear; the ground of the nation has to be prepared for fascism to grow. Donald Trump has offered American citizens an invaluable opportunity: to stare into the ugly reflection of our national consciousness and ask ourselves deep and difficult questions about how, when, and why this consciousness went to seed. What elements of our national histories, values, and truths have led our country––and our planet––to this dangerous political precipice? And how can opening channels of communication for questioning these elements hold us back from the edge?

Kaleidoscopic Truths

On January 20, 2017, the day of Donald Trump’s inauguration, I received the gift of a new technique for exercising one’s inquisitive faculties from organizers at an event at the Joan Mitchell Center in New Orleans: the kaleidoscope conversation. A unique form of roundtable, the kaleidoscope is a stream-of-consciousness dialogue of questions without answers. Starting from a seed question, questions unfurl as participants weave a quilt of their collective subconscious, enriched by the denial of the illusory gratification of instant answers. What I find profound about the kaleidoscope is its ability to respond to complexity, unearthing and articulating that which is foundational yet hidden or unacknowledged. The process of chipping away, winding deeper into spirals of thought, reveals questions we didn’t know we had.

The conversation held that day at the Center was organized around the subject of displacement, a familiar topic of discussion in New Orleans, a city where 249,000 residents, myself included, were displaced by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Participants questioned the gambit of interlocking relations between displacement and race, gender, education, cultural appropriation, wealth disparity, and many other issues, but no one, even on this unusually sweltering 80-degree January afternoon, questioned the connections between displacement and climate change. As Katrina’s wrath was a direct result of environmental degradation and was likely exacerbated by climate change, this gap in our collective consciousness loomed large. That afternoon, I fell in love with the kaleidoscope conversation, imagining the tool as a divining rod with the power to reveal those questions we do not think or dare to ask, those truths that are too frightening to admit. What do we do now?––the refrain heard across America, the world, and within my own head. We are all yearning for answers, but maybe we can’t find them because we haven’t yet asked the right questions. Would these unaskable questions, I wondered, be the most critical for us to hear?

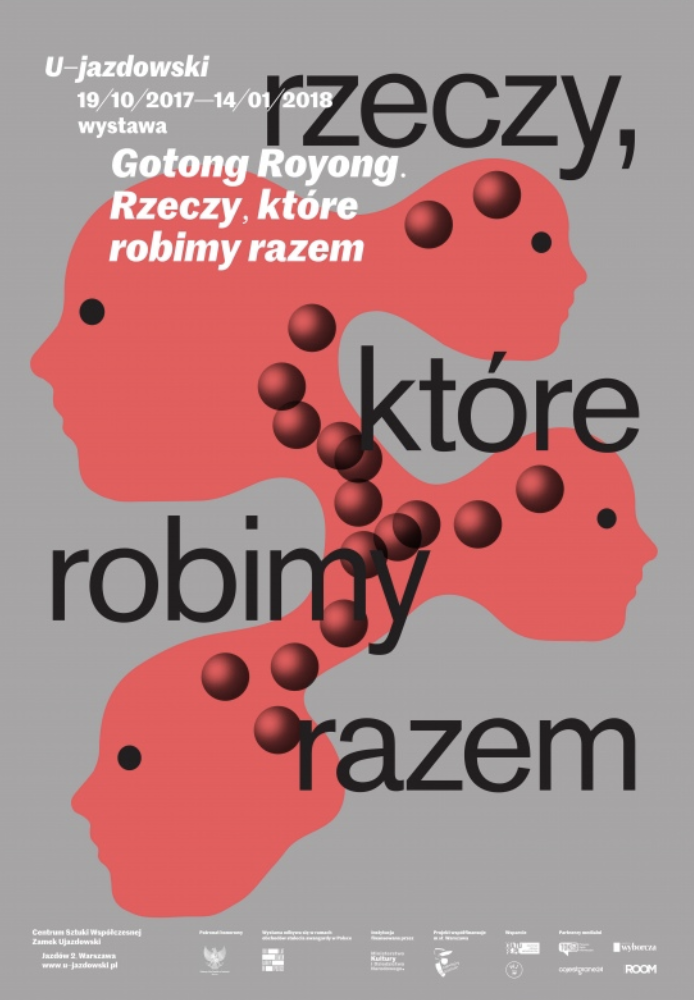

In 2017, I was invited to a month-long residency at the Ujazdowski Center for Contemporary Art in Warsaw, Poland, to participate in an exhibition and public program called Gotong Royong, titled after an Indonesian phrase denoting mutual aid and commonly translated as “things we do together”. My project wanted to question who “we” were and how we understood “together”. Called Truth as Theatrical Fiction,I posited that the rise of global fascism is related to the inability or refusal of individuals and society-at-large to ask questions of ourselves, our authority figures, and our “truths”. For one month, I organized weekly kaleidoscope conversations at the CCA with groups of artists, activists, students, professors, and the general public––self-described “leftists”––from seven nations: Brazil, Canada, Germany, Indonesia, Japan, Poland, and the United States. In most of our homelands, national politics were taking a sharp right turn. In Poland earlier that summer, thousands of Polish fans of America’s newly inaugurated president were bussed to Warsaw to hear him speak; they greeted Trump with uncannily out of place chants of U-S-A, U-S-A and Trump flirted back, quoting lines from a popular Polish song titled “We Want God”. On November 11, the day before our second kaleidoscope conversation, 60,000 people gathered in Warsaw for the city’s annual Independence Day march––this year themed “We Want God”. The cry of “We Want God” rang out amid chants calling for a transnational brotherhood of “White Europe” and white smoke from M14 smoke grenades that turned pink under the glow of panic-red flares.

“We are all yearning for answers, but maybe we can’t find them because we haven’t yet asked the right questions.”

14 Characteristics

Were all of the attendees of the march supporters of the fascist cause? If not, what had brought them there and how do they identify themselves? How did these people come to be on “the other side” and how did we come to be “on our side”? Whose responsibility is it to talk to them? We spend so much time trying to explain them, but who are we? What are our values and how do they distinguish “us” from “them”? Despite immense historic and cultural divides, for we kaleidoscope conversationalists so many of the same questions could be asked of our own nations. How could we comprehend these forces rising up around us? The seed for our kaleidoscope conversations was Italian philosopher Umberto Eco’s 1995 article for the NY Review of Books, which outlines characteristics of Ur-Fascism or “eternal fascism”:

1. Syncretic (or fusion) traditionalism, 2. Rejection of modernism and irrationalism, 3. An appeal to action for action’s sake, 4. Condemnation of critical discourse, 5. Fear of the “other” and racism, 6. Appeal to an economically frustrated or politically humiliated middle class, 7. Nationalism and obsession with a plot, usually an international one, 8. Simultaneous humiliation by the strength and mockery of the weakness of the enemy, 9. Permanent warfare, 10. Popular elitism, 11. The myth of the everyday hero, 12. Machismo, 13. Selective populism, and 14. Reduction of language to Newspeak.

An undercurrent throughout Eco’s characteristics is a stalwart conviction in a mythic “truth” and the refusal or incapacity to examine it through the self-questioning mechanism of critical thought. The difference between factual truth and emotional truth could be framed as the difference between “the truth” and “my truth”, reason and reaction, information and propaganda. A lack of distinction between the two frameworks seeps into our everyday thoughts and speech in a predicament where, as Noam Chomsky has written, “the general population doesn’t know what’s happening and it doesn’t even know that it doesn’t know”. We like to believe we know what’s really happening and we furnish our private corner of reality with a curated suite of experiences, narratives, assumptions, and facts that become our “truth”. To say that “truth is a theatrical fiction” does not imply that there is no such thing as truth, admit that we are “post-truth”, or deny the wealth of common knowledge, but rather recognizes that fictions often become entangled with and indistinguishable from the “truths” that form our worldviews and that we perform in our politics. How many of our national and personal truths are theatrical fictions?

“Political language…is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.” – George Orwell, Politics and the English Language

One of the mythic truths of 21st century American jingoism was found out to be a lie: the Bush Administration’s insistence that Saddam Hussein was amassing weapons of mass destruction. Yet the revelation on March 15, 2003 that the evidence was forged was not enough to save Iraq from US invasion on March 20, 2003; the sovereign nation’s leader, Saddam Hussein, from summary execution in 2006; or the death of approximately 200,000 civilians since the war began sixteen years ago. Beyond the immeasurable human cost, the Iraq War had by 2010 released almost as much CO2 as a “small scale” nuclear war.

On September 14, three days after the September 11th attacks, Congress passed an Authorization of the Use of Military Force (AUMF) Against Terrorists, a 320-word (including headers) bill that enabled endless war with intentionally broad targets and parameters:

That the President is authorized to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations or persons.

“[Barbara] Lee warned against succumbing to fear, the eternal seed that fertilizes the ground for fascism to take root.”

Congresswoman Barbara Lee, a black Democrat from California, was the only member to vote “nay”. In a post-vote speech to Congress, Lee acknowledged that “September 11 changed the world. Our deepest fears now haunt us,” but urged Congress to “pause just for a minute and think through the implications of our actions today so that this does not spiral out of control.” While every single other voting member of the House and Senate (518 representatives, including independent senator Bernie Sanders) voted in favor of a state of exception, Lee warned against succumbing to fear, the eternal seed that fertilizes the ground for fascism to take root. “Action,” Eco writes about Characteristic #3, action for action’s sake, “must be taken before, or without, any previous reflection. Thinking is a form of emasculation.” The AUMF laid the groundwork for subsequent blows to the US Constitution from the USA PATRIOT Act, illegal spying by the NSA, the persecution of whistleblowers, and the 2012 NDAA (National Defense Authorization Act), which authorized the indefinite military detention of persons the government suspects of involvement in terrorism, including U.S. citizens arrested on American soil. Lee’s stalwart stance garnered commendations from her constituents, but troublingly, accusations of treason were equally forthcoming. As Eco notes in Characteristic #4, Condemnation of critical discourse, “for Ur-Fascism, disagreement is treason.” For nearly two decades since that fateful collective decision to act decisively without question, war has marched on with no end in sight, even as targets morph and battlefields expand to encompass more than 100 nations, according to Jeremy Scahill in 2013 (Characteristic #9, Permanent warfare).

Do you remember this moment in time? In October 2001, 89% of Americans across the political spectrum were polled as supporting the War on Terrorism. We were scared so we did as we were told, stocking up on duct tape and plastic wrap in response to color-coded threat levels. In defiance of this fear, we built ourselves up as defenders of the nation and eagerly reported the “suspicious activity” of our neighbors (Characteristic 11. The myth of the everyday hero). At home in New Orleans, a city that long prided itself on its multinational and multiethnic culture that was so unlike the rest of America, my middle school sang “I’m Proud to be an American” at the beginning of every single morning assembly for the entirety of my 8th grade year (Characteristic 13. Selective populism).

Do you remember this moment in time? In October 2001, 89% of Americans across the political spectrum were polled as supporting the War on Terrorism. We were scared so we did as we were told, stocking up on duct tape and plastic wrap in response to color-coded threat levels. In defiance of this fear, we built ourselves up as defenders of the nation and eagerly reported the “suspicious activity” of our neighbors (Characteristic 11. The myth of the everyday hero). At home in New Orleans, a city that long prided itself on its multinational and multiethnic culture that was so unlike the rest of America, my middle school sang “I’m Proud to be an American” at the beginning of every single morning assembly for the entirety of my 8th grade year (Characteristic 13. Selective populism).

And then, March 19, 2003: Shock and Awe. I was fourteen years old, in 9th grade Environmental Science class, and the television news was on, a new normal in this era of, to use Eco’s framework, “TV or Internet populism”. My classmates stared at a grainy, green-tinted display of cluster bombs exploding over Baghdad, cheering as though watching a fireworks display on the Fourth of July. Now that the WMDs were out of the picture, we were told that we were bringing the Iraqis freedom. Liberating them. Whatever the truth was, we knew were winning and there was cause for celebration. (Characteristic #8, Simultaneous humiliation by the strength and mockery of the weakness of the enemy.) The political scene was tectonic and when the entire surface slipped to the right, liberals and conservatives alike moved with it.

How do we understand the spectrum from patriotism to fascist nationalism? We can look to the disinformation campaigns of the War on Terrorism to understand that the conflation of truth and “alternative facts”, among other characteristics of fascism, didn’t begin with Donald Trump. We are looking at the extremes rather than questioning the core. Yet while the ground for fascism was fertilized by our response to 9/11, which declared Islam, and any brown person associated with the faith, the enemy (Characteristic #5. Fear of the “other” and racism), it didn’t begin there either. Consider the recently well-documented scourge of white female vigilantes, aka “Beckys”, reporting black folks to the police for the “crimes” of selling bottled water, swimming, barbecuing, and cheering their children on at sports games. While Becky’s nosiness shares a sensibility with post-9/11 appeals to “see something, say something” (Characteristic 11. The myth of the everyday hero), it also continues an older American trope: white women falsely accusing black people of crime. Indeed, long before 9/11, Jim Crow policies inspired the Nazis’ race laws.

If fascism can only take hold in societies whose citizens have ceased to question their nation’s foundational “truths”, then we need to directly and unflinchingly question these narratives in order to move forward.

Over the past two years, we have weathered the heightening of foreign and domestic policies that have pulsated throughout our short history––policies that have been implemented and exacerbated by Democrat and Republican administrations. It’s not enough to be against a border wall when proposed by Trump but not Clinton. It’s not enough to oppose a Muslim ban but support regime change in the Middle East. To say that we need to look at the roots of global fascism does not dilute the urgency of today’s political moment nor equivocate between the impact of a Republican or Democrat presidency, but rather offers a third proposition. 2019 is a critical year not only for the future of democracy, but for the future of humanity. Climate change demands that we fundamentally transform the carbon-heavy values of our society, and our nation’s militant nationalism, mobilized by our grotesquely muscular $716 billion military, the world’s single greatest emitter of carbon dioxide, is a great place to start. If fascism can only take hold in societies whose citizens have ceased to question their nation’s foundational “truths”, then we need to directly and unflinchingly question these narratives in order to move forward. Let’s make 2019 a year for interrogating our personal support for virulent theatrial fictions. And, if you find the idea intriguing, consider organizing your community in a kaleidoscope conversation.

[/cmsms_text][/cmsms_column][/cmsms_row]